Architecture reveals itself most clearly at the moment it allows something to pass through it. Light, air, view, a body, time.

Architecture reveals itself most clearly at the moment it allows something to pass through it. Light, air, view, a body, time.

An opening is never neutral. It is not simply the absence of wall, or floor or roof. It is an act, a decision, a position taken on how a building relates to the world beyond it - how you will relate and interact and how the outside will interact with you.

In much contemporary work, openings are the result of division. Walls are split apart, pulled back, erased in service of plan, program, or transparency.

There is another way of thinking about openings. One that begins with the assumption that the wall matters.

To pierce a wall rather than divide it is to first acknowledge its mass, its weight, its continuity - its integrity. The opening is not made by separating, but by carefully cutting into something whole - something valuable. It is less violent, more deliberate, and often quieter. The wall remains present, and the opening gains meaning because of it.

This distinction, subtle as it may appear, produces very different atmospheres.

Louis Kahn was the master of the opening. In his Bangladesh parliament in Dhaka, openings are simultaneously sculptural and graphic. The walls remain heavy, almost immovable, and yet they are alive with openings that feel inevitable and expressive. At the Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad, apertures are treated as moments of passage and compression. The thickness of the wall becomes a place in itself, a zone where inside and outside briefly coexist.

Elsewhere, Claudio Silvestrin’s Neuendorf House in Majorca operates with similar consideration. Its openings are celebrated and deliberate characters: sometimes they are measured incisions within continuous surfaces, other times they appear as slices cutting walls in two.

What these projects share is a respect for mass. A belief that architecture begins not with void, but with substance.

Within our own work, we have explored both approaches. We have split walls open to create generosity and connection. We have also pierced them, carefully, to test how little is required to admit light, view, or movement. Over time, the difference has become increasingly apparent, not just visually, but experientially.

As our work evolves, we are consciously moving away from buildings that read as extrusions of the floor plan. Plan remains essential, but it is no longer sufficient. We are more interested in architecture as a three-dimensional condition, where walls are volumes, not lines, and openings are shaped with intention.

An opening asks a question of a wall. How much can be removed without diminishing what remains? How deep must it be to feel generous rather than exposed? How can it admit the world without surrendering the room?

These are modest questions, but they carry weight. They affect how a space feels at different times of day. They shape how we move, where we pause, and how architecture reveals itself slowly, over time.

I was listening to a podcast today. Not on architecture. I tend to avoid design content when I am trying to switch off because it leaves me more agitated than relaxed. But one word in this unrelated conversation caught me: temporariness.

I was listening to a podcast today. Not on architecture. I tend to avoid design content when I am trying to switch off because it leaves me more agitated than relaxed. But one word in this unrelated conversation caught me: temporariness. It stayed with me. The term is both fleeting and grounding, a reminder that the moment is always moving and yet still available to be noticed. Thinking in terms of temporariness lifts you out of distraction, then returns you to the present with greater clarity.

We move quickly. We rush from task to task, place to place, absorbed in our screens and the immediacy of what is required. It feels like presence, but it is not. We are attentive to the task rather than the atmosphere. The mind is full, but not mindful.

Temporariness reveals how the here and now is always shifting. Sometimes this is dramatic: a storm breaking open the sky, a burning sunset, a full moon rising. These moments grip us, then fade.

More often, temporariness is subtle. A cloud softening the light. A quiet shift in colour from morning to afternoon. The slow movement of leaves casting patterns across a room. These small changes are where most of life unfolds.

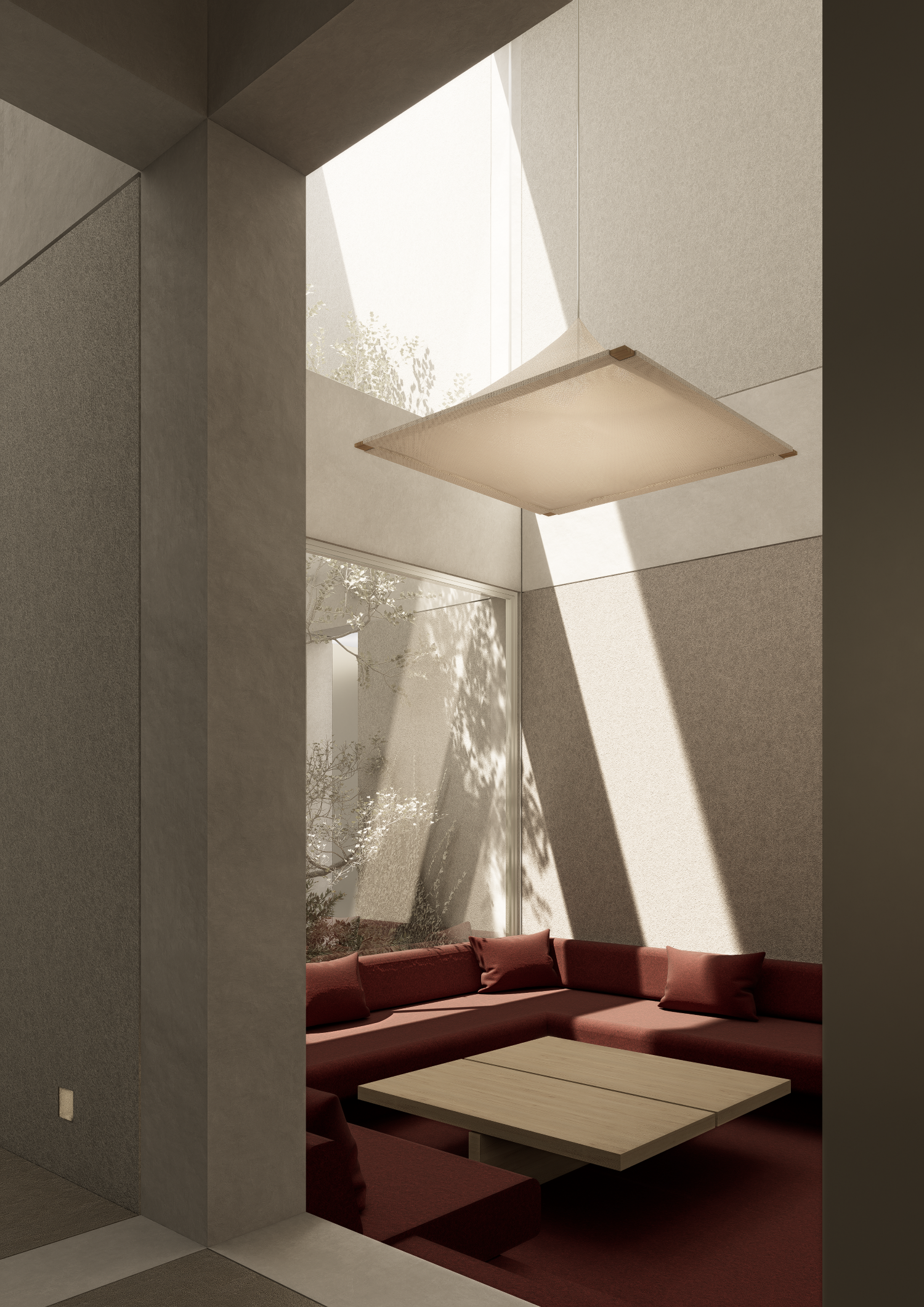

Architecture becomes meaningful when it is designed to receive these shifts. A walled courtyard that captures the movement of the weather and turns the sky into a kind of theatre. A large skylight that frames the heavens and makes passing clouds legible. A deep reveal that slows the transition from inside to out. These elements anchor us by giving form to what is otherwise easy to overlook.

To design with temporariness in mind is not to seek spectacle. It is to make the ordinary visible again. It restores the capacity to notice the world as it changes around us.

The temporary is always there. Architecture, at its best, helps us stay conscious of our place within it.

This piece began as a conversation.

Last month, Hannah Abbott from Otomys invited me to join a panel discussion with Helen Redmond as part of Still Point, the exhibition marking the gallery’s fifteenth anniversary.

This piece began as a conversation.

Photographed by Bernie Wright

Last month, Hannah Abbott from Otomys invited me to join a panel discussion with Helen Redmond as part of Still Point, the exhibition marking the gallery’s fifteenth anniversary. Sitting beside Helen, surrounded by her paintings, I realised that the themes we spoke about that afternoon reached far beyond the event. They touched on the foundations of my architectural education, the buildings that shaped me, and the way I think about light, order and restraint.

My connection to Helen’s work is longstanding. I have admired her paintings for many years and am fortunate to live with one. It hangs in our meeting room, directly behind me when we present projects. Her work feels familiar not because it depicts recognisable spaces, but because it captures something essential about how space behaves. The paintings are distilled rather than descriptive, built from simple forms and planes, yet animated by the way light moves across them. Shadows soften unexpectedly. A ceiling glows where logic suggests it should fall into shade. Surfaces hold both clarity and mystery. The work is neither photographic nor digital. It belongs to a different language, one that speaks in atmosphere rather than representation.

Seeing a new series that Helen had painted specifically for Villa Alba brought me back to an early moment in my training. When I finished my studies, a tutor encouraged me to visit two buildings: Peter Zumthor’s thermal baths at Vals and Le Corbusier’s monastery of La Tourette. I had studied them academically but experiencing them was transformative. I arrived at Vals late at night with no camera, which now feels like a gift. The next morning the building revealed itself slowly. Water tracked across stone. Light was treated almost as a rare commodity, slipping into dark corridors, halls and rooms in a way that amplified its presence. It was architecture understood not through image but through sensation, and it left an impression I have never quite shaken.

La Tourette offered a different lesson. Where Vals felt elemental in form, La Tourette was elemental in ritual and culture. Its concrete frames carved the sun into narrow intervals, dividing time as much as space. Light there was disciplined and structured, almost liturgical. Together, these two buildings taught me that architecture is not only the arrangement of volumes but the shaping of light, proportion and restraint. They formed the early architecture of my thinking long before I knew what my own work might become.

This is why Helen’s paintings struck me so strongly when I first encountered them. They echoed that early experience. They captured the way light misbehaves, how it ignores diagrams and reveals unexpected qualities within the simplest forms. Her work is a study of what happens when form becomes a vessel for atmosphere. In that sense, the paintings feel closer to architecture than to image making. They are a reminder that light is always the true subject.

In our practice, this pursuit of light is shaped by constraint. Every project begins with a site, a family, a budget and a set of competing needs. These limits are not obstacles. They are the conditions through which meaning emerges. Within them lies the opportunity to create spaces that breathe, that register the seasons and the passing of the day. The most poetic moments often occur in the in-between spaces, the corridor, the entry, the stair. These are the places where contrast, shadow and proportion can work quietly and powerfully.

Technology has changed how we communicate this intention. For years, restraint was difficult to show. Clients would look at early renders and search for the design, assuming that simplicity meant incompleteness. As our ability to model the movement of natural and artificial light has improved, we can now show how a room transforms across the day, how material and light work together, how clarity can be more expressive than complexity. Light becomes the organising principle.

During the panel at Otomys, we spoke about this shared territory between painting and architecture. Sitting among Helen’s work, I was reminded that both disciplines are attempts to capture the intangible. Both search for that moment of alignment when form and light settle into equilibrium. In architecture I often think of this as the still point, the moment a project reveals its essence, when proportions start to cohere and the dread of the blank page turns into the excitement of emergence.

This is the pursuit that connects Vals, La Tourette, Helen’s work and our own practice. It is the search for clarity within complexity, for atmosphere within structure, for light as the quiet protagonist. The buildings that shaped me early on taught me that architecture becomes meaningful when it transcends function and enters the realm of experience. Helen’s paintings remind me of this every day.

We speak often about buildings, but rarely about architecture.

We discuss housing supply, heritage overlays, budgets and schedules; the tangible mechanics of building, yet seldom the invisible qualities that truly define it: space, sequence, light, proportion, the way a room opens or holds its breath.

We speak often about buildings, but rarely about architecture.

We discuss housing supply, heritage overlays, budgets and schedules; the tangible mechanics of building, yet seldom the invisible qualities that truly define it: space, sequence, light, proportion, the way a room opens or holds its breath.

This absence says something. Architecture is the most public of the arts, yet it attracts the least conversation. A painting hangs in a gallery; a building frames our lives. We walk through it, rely on it, inherit it. And still, we seldom pause to talk about what it means - what it does to us. Perhaps we take it for granted. Or perhaps, as with many of the arts, it has been gently side-lined, replaced by conversations about efficiency, cost and compliance.

But architecture is a barometer of culture. It records what a people value - its priorities, its aspirations, its spirit. Every era leaves a spatial trace of itself. When a culture stops talking about architecture, it stops asking what kind of world it wishes to inhabit.

Too often, the conversation that remains is about size and status - how large a house is, how many bedrooms or bathrooms it holds, how many Instagram-able moments it contains. We talk about finishes, not light; inclusions, not atmosphere. Yet these metrics say nothing of how a home actually performs - how it feels, how it breathes, how it shelters. The absence of this deeper dialogue has reduced architecture to inventory, when its real measure has always been experience.

Louis Kahn once said, “A great building must begin with the unmeasurable, must go through measurable means when it is being designed, and in the end must be unmeasured.” In his work, walls hold light as if in conversation - silence made visible. His buildings remind us that architecture is not just about function but about dignity, about giving shape to human experience. To talk about architecture, then, is to talk about time itself: how we live within it.

This is not to romanticise the discipline or ignore its practical demands. Architecture will always be tethered to construction and cost, to regulation and delivery. But the conversation could afford to reach further - to speak of atmosphere, material, and meaning. To ask not only what we build, but what we are aiming to create beyond the mere brief.

The loss of that conversation is not only to architecture’s detriment; it is everyone’s. When discussion narrows to procurement and façade, imagination is limited and numbed. We begin to see buildings merely as commodities. Yet architecture at its core is about achieving more, more than the brief, more than compliance, more efficiency, more GFA. How do you add delight, intent, craft and care? How do you make a space worthy?

Perhaps architecture’s quietness has worked against it. Unlike theatre, music, or film, it doesn’t demand our attention all at once. It often reveals itself slowly, across seasons, through occupation and use. But that slowness is also its gift. It asks us to notice - to tune our senses to the way light falls on a wall, or how a threshold shifts the mood of a room. In a world increasingly distracted, architecture’s patience might be its most radical quality.

To revive the conversation is not to intellectualise the everyday, but to reawaken curiosity. To ask: how does this space make me feel? What does it allow? What does it deny? These questions belong to everyone, not just architects.

If art can stir emotion, if music can bind memory, then architecture can ground us. It can lend coherence to our daily rituals, shape our sense of belonging, and quietly mirror who we are.

Perhaps, then, the missing conversation is less about architecture itself, and more about us, about what we choose to notice, to value, and to build.

Among all the spaces that make up a home, the entry is perhaps the most overlooked. It rarely appears in a client’s briefing document. Yet it is the first and last moment of every visit, the space that negotiates between the world outside and the life within.

Among all the spaces that make up a home, the entry is perhaps the most overlooked. It rarely appears in a client’s briefing document. Yet it is the first and last moment of every visit, the space that negotiates between the world outside and the life within.

When we begin to plan a home, the location and composition of the entry are critical. In this small zone, many different performances unfold: waiting for the door in the rain, greeting a group of guests, lingering for farewells and doorway conversations, slipping on shoes, or presenting flowers and a bottle of wine. The entry is a small stage - sometimes with a cast of many, often with only one actor - where architecture must quietly manage light, movement, and mood.

From a planning perspective, we look to accommodate not just the ergonomics of these rituals but the emotion that accompanies them. The entry should offer shelter and privacy, a moment of pause that smooths the transition from public to private life. It must be practical yet ceremonial, allowing for everyday comings and goings while still holding a sense of grace. A light that spills across the threshold, a covered step, the sound of a door closing softly - all these small gestures signal welcome and belonging.

Architecturally, the entry is both a space for standing and a space for passing through. It holds stillness and movement at once. We often draw on Frank Lloyd Wright’s idea of compression and release - a sequence that moves from dark to light, from narrow to open. This rhythm creates intimacy and drama in quick succession, preparing the body and the mind for what lies beyond.

A well-designed entry is not simply an access point but an emotional calibration, a first act that sets the tone for the rest of the home.

In several recent projects, we have explored how the entry can also test the boundaries between inside and out. By manipulating light, enclosure, and view, the threshold becomes ambiguous - part garden, part room. Screens, courtyards, and overhangs allow the space to breathe, extending the welcome before one even crosses the door. In this way, the entry continues the conversation we began with the courtyard: both are transitional territories that invite a slower rhythm of arrival and departure.

At its best, the entry performs two tasks simultaneously. It must function with absolute clarity - logical, sheltered, effortless - yet it should also evoke emotion, creating the briefest moment of theatre in the everyday act of coming home. For all its modest size, the entry remains a deeply human space, one that reminds us that architecture begins not with walls, but with thresholds.

Architecture and the interiors it holds are inseparable. The most compelling work reads as one thought carried through many scales, from the composition of the plan to the turn of a handle.

Architecture and the interiors it holds are inseparable. The most compelling work reads as one thought carried through many scales, from the composition of the plan to the turn of a handle.

The idea is ancient, but it found its distilled form in the modern tradition of the Gesamtkunstwerk: the total work of art came into vogue in the late nineteenth century. To invoke it today is not a call for excess or control, but for coherence. A building should feel inevitable, as though plan, section, detail and furnishing were all born of the same language, the same hand.

In practice, this means working from the outside in and the inside out at once. Site, climate and program set the first conditions. From there, form and threshold establish how the building meets light and landscape. Grammar and punctuation follow: the structure’s expression, the significance of a junction, the invitation of shadow, the dialogue between materials.

At the interior scale, the same language is held. Materials are restrained so each becomes essential. Details repeat so the eye can rest and the hand can predict. A stair set into a slab, the return of a cabinet, the turn of a rail, all carry the same consistency of thought. With this foundation in place, loose pieces can enter freely and with confidence.

Furniture, lighting and art are not always part of the commission, but increasingly they become part of the process. Clients often invite us to help assemble collections or design key pieces that complete the rooms. Recent travels, including Milan Design Week and the development of our own furniture, have sharpened that focus. We are drawn to pieces that work harder than they look, that hold material truth, and that continue the architectural conversation across scales.

Our pursuit is not the totalising ideal of a century ago. Life resists perfect control, as it should. The ambition is quieter: to hold a clear vision across scales so that a house feels calm, legible and incomplete in a way that allows for change and evolution over time. Architecture that sets the tone. Interiors that resonate with it. Objects that belong, enhance, and allow life to unfold.

Heidi Museum of Modern Art

Last month I had the privilege of speaking at the IID’s annual conference, hosted at Tollmans. My sincere thanks to the IID for the opportunity, and to Tal Goldsmith Fish for the kind invitation.

Last month I had the privilege of speaking at the IID’s annual conference, hosted at Tollmans. My sincere thanks to the IID for the opportunity, and to Tal Goldsmith Fish for the kind invitation.

In preparing for the talk, Tal suggested that the audience might enjoy case studies of Australian homes. That prompt led me to revisit our work of the past decade through the lens of Australian Modernism; a theme that has long shaped how we design.

Alongside our own projects, I highlighted works that have been enduring influences, including Harry Seidler’s Killara House and McGlashan Everist’s Heide II. Taking the time to reflect on these precedents, and on the homes we have designed both on the Mornington Peninsula and in more urban settings, was a welcome gift.

What struck me most came after the talk, in conversation with colleagues. I was surprised; in the best possible way, to hear how distinct our work appeared when seen alongside that of our Israeli counterparts. In a world that feels more globalised every day, realising that our architecture continues to carry a clear sense of regional identity was rewarding in itself. It reminded me that architecture is always a dialogue between the universal and the local: informed by global discourse, yet grounded in the particularities of place, culture, and climate. For us, that means embracing the material honesty, spatial clarity, and connection to landscape that have long defined Australian Modernism, while continuing to evolve these qualities for contemporary living. To see that identity recognised by peers from another part of the world was both affirming and inspiring.

In our work, we often seek clarity - spaces stripped of ornament and freed from superfluous detail. Yet, in the quiet of that restraint, a question lingers: when expression and overt context are pared away, how does a space hold on to its vitality? How does it maintain proportion, intimacy, or intrigue?

In our work, we often seek clarity, spaces stripped of ornament and freed from superfluous detail. Yet, in the quiet of that restraint, a question lingers: when expression and overt context are pared away, how does a space hold on to its vitality? How does it maintain proportion, intimacy, or intrigue?

A room is never only a volume. It is a vessel for memory, for light, for the slow passing of seasons. It is the particular quality of shadow in the late afternoon, the sound of footsteps on a timber floor, the faint scent of rain carried in from an open window. These intangible elements are what lend permanence, what allow a space to become not merely functional, but alive.

One of the challenges we often set for ourselves is the play between the familiar and the abstract, the comfort of something expected versus the purity we seek through distillation. To do this, we strip an idea back to its core DNA. We ask: What is this space really about? What makes it work? Once we understand that, we can decide what is essential, and what can be discarded.

That DNA can be found in proportion, materiality, texture, symmetry, acoustics, and the sequence or procession through space. These qualities are not tethered to any one culture or style, yet they can be infused with meaning and manipulated to create emotional resonance.

Proportion is one of our most powerful tools. It’s in the size and placement of an opening in a wall, how it pierces the surface, revealing its depth. It’s in the way light passes through that opening, blending spaces together or holding them apart. It’s in the way a view unfolds, slowly or all at once, leading the occupant from one experience to another.

But restraint comes with risk. Pared-back minimal spaces can easily slip into sterility; cold, clinical, lifeless. For us, the solution lies in looking to the past, not to replicate it, but to reinterpret it. We find lessons in historic architecture: the way light grazes a worn stone wall, the way a timber beam frames a view, the way spaces are shaped to invite pause. These references remind us that simplicity need not be empty; it can be rich, layered, and deeply human.

For us, the enduring moment in any building is achieved through the sequence of spaces, the way they relate to one another, whether clearly defined or softly blurred. It’s in how they respond to what lies beyond their walls: the shifting light, the movement of landscape, the expanse of sky. This orchestration creates something more than shelter. It creates places that live in the memory, spaces that feel inevitable, as if they could never have been otherwise.

In the end, that is the true measure of success: to craft a space that endures. One that is spare, yet vital. One that can be rediscovered again and again, revealing new layers over time. One that is capable of carrying nostalgia; for those who have known it, and even for those who have only imagined it.

Architecture holds space for both perfection and imperfection. Embracing the natural weathering of materials introduces time as a deliberate ingredient in the design. Ageing, patination, and imperfection allow a building to feel more human - connected to its environment and its occupants - rather than frozen at the moment of completion.

This series offers a glimpse into the ideas that shape our work: the role of time, the behaviour of materials, the pursuit of feeling over formality.

Not manifesto, but meditation; a way of sharing what we value, and how we design for life as it is truly lived.

In architecture, the conversations that shape a project often live beneath the surface; decisions about materiality, time, feeling, and restraint that are rarely seen, but deeply felt.

What is a material you love more once it has aged?

Quality, natural materials, detailed with sensitivity and understanding have the rare ability to improve with time. Sun, wind, rain, and the human hand all leave their mark. Materials like leather and timber soften and darken through use; concrete limes and discolours as it settles into place; metals like brass and steel patinate, deepening in richness.

Fresh concrete can look good; but it only feels resolved once it has weathered, begun to lime, and absorbed the atmosphere of its setting. As ivy finds its way across the surface, or rain carves faint patterns, the building begins to feel inevitable. A similar story can be told of brass, steel, and stone. They find their full expression through time, not despite it.

Can you describe a favourite moment when a material surprised you over time?

Travertine is a material we return to often. Its natural pores and pits often lead to questions: should they be filled or left open? Our preference is to leave them exposed. Over time, dust and fine debris naturally settle into the voids, subtly darkening the surface and softening its overall appearance. It is a process that brings an authenticity and depth no synthetic material can replicate. Rather than resisting the character of the stone, time reveals it.

Why is imperfection beautiful in architecture?

Architecture holds space for both perfection and imperfection. Embracing the natural weathering of materials introduces time as a deliberate ingredient in the design. Ageing, patination, and imperfection allow a building to feel more human, connected to its environment and its occupants, rather than frozen at the moment of completion.

How do you design for patina? Do you invite it rather than resist it?

Designing for patina begins with a respect for durability and appropriateness. This operates at every scale: from the choice of wall finishes that will soften with exposure, to a stair tread subtly rounded in anticipation of decades of wear. Some signs of age are celebrated openly; others, such as the softening of a well-used threshold, are anticipated quietly through careful detailing.

If you had to choose: perfect crispness forever, or graceful ageing? Why?

Architecture is not static. Buildings are prototypes of human imagination, crafted by hand rather than machine. Pursuing the illusion of perfect crispness often leads to fragility and disappointment.

We design with an understanding that craft, buildability, and the realities of time are not constraints but opportunities. In that light, graceful ageing is not simply accepted, it is invited.

In Melbourne, landscapes often function as a backdrop, appreciated more for their visual presence than as spaces to actively inhabit. Yet, when thoughtfully conceived, courtyards have the power to transform a home, enhancing both its interior and exterior expressions.

In Melbourne, landscapes often function as a backdrop, appreciated more for their visual presence than as spaces to actively inhabit. Yet, when thoughtfully conceived, courtyards have the power to transform a home, enhancing both its interior and exterior expressions.

Courtyards bring more than landscape into a design; they allow the introduction of air, sky, and light, elements that add depth and vibrancy to a floor plan. Their presence creates an opportunity to shift the spatial experience, blurring the boundaries between indoors and outdoors and fostering a dynamic relationship with the natural world.

The role of a courtyard is often defined by how it engages with the spaces around it. Some are designed as active extensions of living areas, hosting gatherings, meals, or quiet moments of recreation. Others take on a more contemplative function, offering framed views of a lush garden, a sculptural centrepiece, or the shimmering surface of a water feature.

These spaces might reveal themselves slowly, with glimpses through carefully framed openings, where shards of light and shadow dance across walls, or they might be bold and transparent, functioning like a 'fishbowl' that connects expansively to its surroundings.

Equally important is how the courtyard sits within the architecture itself. The transition between indoor and outdoor might be seamless, with flush thresholds that invite continuity, or slightly stepped, creating subtle separation. Windows and doors become more than functional - they frame the courtyard, shaping how it is experienced from within.

Some of our favourite courtyards are below.

LDS Residence I

To mediate the transition between the rear of the house and the swimming pool and tennis court beyond, we designed a cloistered courtyard that extended the house through two covered areas. The first served as an extension to the meals area, while the second connected to the living room and featured an outdoor fireplace. The open space between these areas was left exposed to the sky, housing an ornamental garden that brought a sense of calm and elegance to the design.

EPSC Residence

Situated on a steeply sloping site, this house was designed around two courtyards to allow light and air to penetrate the spaces. The first courtyard is small and private, offering a quiet retreat, while the second is larger and highly functional. Acting as the entry point to the house, the larger courtyard serves as an enclosed outdoor room, providing shelter from the strong winds characteristic of the site.

LPS Residence

In this rural home, the courtyard was envisioned as a central element, creating a transition between the vast openness of the surrounding property and the intimacy of the interior spaces. This courtyard became a unifying feature, linking the expansive natural landscape with the comfort of the home’s living areas.

JDF Residence

One of four courtyards in this house, this central courtyard acts as a focal point, visible from the entry and meals area. It also includes a covered dining space, offering both functionality and a striking visual anchor within the home.